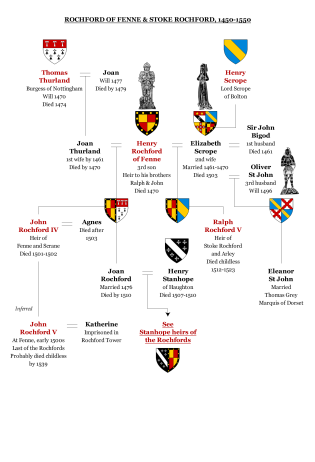

← Previous: Henry Rochford of Fenne (died 1470)

Henry Rochford’s three children were still minors when he died, although there are few records to help establish exactly how old they were. The eldest, John and Joan, whose mother was Henry’s first wife, must have been born between about 1450 and the late 1460s (Joan’s own son Edmund would be born by 1484 at the latest). Their younger half-brother Ralph, meanwhile, must have been born between 1462, nine months after his mother Elizabeth’s previous husband was killed at the battle of Towton, and 1471, nine months after his father died.

On Henry’s death John and Joan became orphans. Under the terms of his earlier settlement of the manor of Fenne, this property was to be their inheritance – or John’s, at least. So they and the property fell to the guardianship of their overlord there, who was now Edward IV’s duplicitous brother George duke of Clarence. In December 1470 the duke granted the manor and the two wardships to Thomas Tothoth, who in turn granted them to the children’s grandfather, Thomas Thurland, who was still alive despite having written his will earlier in 1470. Thurland no doubt paid a pretty penny for this, but he must have felt safer in the knowledge that he had his Rochford grandchildren and their inheritance in his own care while the civil war raged on.

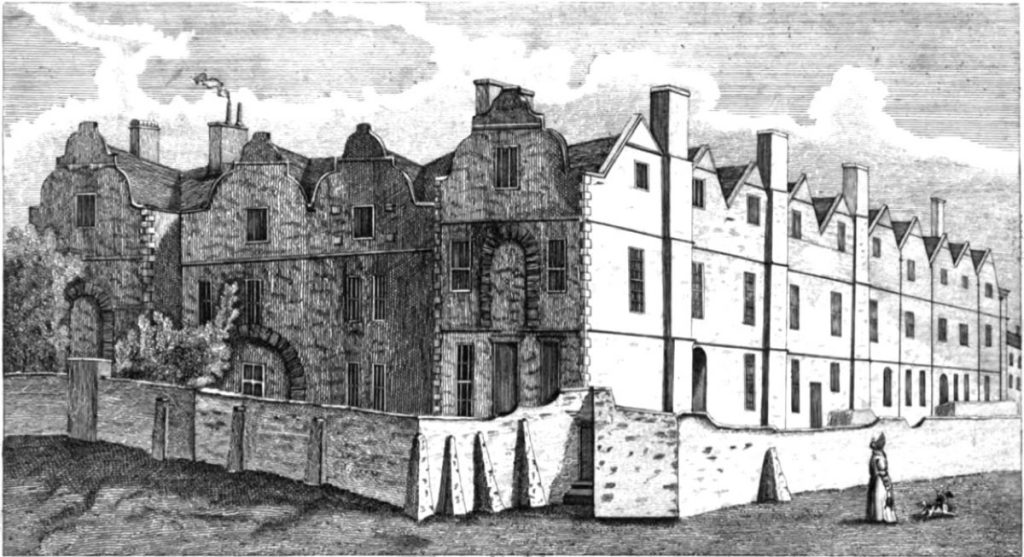

John and Joan Rochford probably lived with their grandparents at Thurland Hall, the enormous house in Nottingham that Thomas Thurland had built in the mid-1400s. Thomas died a few years later, on 5 January 1474, and he was buried in St Mary’s church, Nottingham, where parts of his tomb still remain today. In his will, he left £20 each to his two Rochford grandchildren.

Four years later, on 8 June 1477, the siblings’ grandmother “Dame Joan Thurland”, as she called herself, wrote her own will. She left several affectionate gifts to John including “a standing maser covered with an eagle over the top of the covering” – it was a type of drinking bowl similar to a chalice. She also left him “four coverlets with trefoils” and some other soft furnishings, which, she wrote, “I have put in his chest to be kept there”. This suggests that John still lived with his grandmother, rather than at Fenne, so perhaps he was born after about 1456. John’s sister was not mentioned in the will, probably because she had already been well provided for in marriage the year before – we will return to this shortly. The old Joan Thurland died a year or so later. Her will was proved on 21 July 1479.

During these and the following years the face of English government would change forever. The insane Lancastrian King Henry VI had died in the Tower of London on 21 May 1471 – in all likelihood he was murdered. His nemesis, Edward IV, died twelve years later in 1483. Edward’s two young sons, Edward V and Richard, disappeared shortly afterwards into the Tower of London, never to be seen again. They were perhaps murdered by their uncle, who now became king as Richard III. But two years later a young earl of Richmond named Henry Tudor returned from exile in Brittany with a small army to claim the throne as the heir of the Lancastrian kings. On 22 August 1485 King Richard’s head was bashed in on the field of battle at Bosworth, and his crown was put on Henry’s head. So the Tudor era began: this was Henry VII. Like Henry IV in Sir Ralph’s time, the new king quickly elevated those who supported him to important local and national roles, and he destroyed any who did not. He would become the coldest, meanest, most calculating sovereign England had known since Richard II.

We might expect the young Rochford brothers to have played a role in all this – especially because of their family’s long, interwoven history with the Lancastrian dynasty. But they were nowhere to be seen. John and his half-brother Ralph Rochford had more in common with their father, Henry, than their energetic ancestors. There are almost no records of them. They assiduously avoided royal, political and local affairs, and they stuck to being well-to-do landed country esquires.

When John came of age he inherited the manor of Fenne as per the family arrangements, and as Henry’s eldest son and heir he also inherited the manor at Scrane. But the properties at Stoke Rochford and Arley remained with his step-mother, Elizabeth Scrope, and they would later pass to Ralph, under the deal most likely made when Henry and Elizabeth married. This was completely contrary to common law and the norm: to John, this could only have looked like a form of disinheritance, a snub to the fact that his own mother, Joan Thurland, was of lower status than his step-mother. And to add insult to injury, later records suggest that the estates Ralph inherited were half as large again as the ones John received. We know nothing of John’s character, but he had a good excuse if he was bitter.

In October 1494 John was recorded at Toft in an inquisition taken after the death of his neighbour John Coppledike, who held six acres of land in the parish under him. Then, over a series of transactions between 26 June 1497 and 12 November 1501, “John Rochefort, Squire of Fenne beside Boston, county Lincoln, son and heir of Henry Rochefort, son and heir of Sir Ralph Rochefort” sold his entire inheritance to a gentleman from London named William Essington. The records of these transactions provide some insight into the extent of the estates at that time. In the first transaction, in 1497, John sold Essington the “manor of Skrenyng in the parishes of Toft and Friston, and certain parcels of the manor of Fenne beside Boston”, described in total as “one messuage, twenty acres of land, 100 acres of meadow, 100 acres of pasture and four shillings of rent in Skreyng, Boston, Toft, Skyrbek and Fryston” for £170. The next year he sold Essington the much larger “manor of Fenne and twenty messuages, one mill, one dovecot, one garden, 600 acres of land, 500 acres of meadow, 1000 acres of pasture and six pounds of rent in Fenne, Tofte, Boston, Skyrbek, Fryston, Butterwyke, Bennyngton and Sybsey and the advowson of the church of Fenne” for £467 6s 8d. The total size of the estates described adds up to 21 houses, 2320 acres, £6 4s rent and assorted extras. The total value of the sale, at £637 6s 8d, was huge. In 1501 these transactions were repeated or confirmed – perhaps there was some aspect to the title that had remained unclear.

Soon after, between 12 November 1501 and 25 November 1502, John died. He cannot have been very old – he was probably between about 31 and 46 years of age.

John left a widow, Agnes, who evidently still had an interest in her late husband’s property. After his death she conveyed the same “manors of Fenne and Skreyng” with exactly 21 houses, 2320 acres and £6 4s rent to Richard Foxe, the bishop of Winchester. In January 1503 the deal between Agnes and the bishop was completed, and around the same time William Essington sold his rights in the property to the same bishop. Foxe was acting as an intermediary for Westminster Abbey: on 14 December 1503 the abbot, John Islip, wrote to William Essington confirming their purchase of the manors of Fenne and Scrane worth £44 pounds a year, for a total £578, of which £73 6s 8d was still to be paid. He wrote that the purchase was “towards the perfourmyng of the Wyll” of King Henry VII.

The “will” of Henry VII in this case was his famous memorial at Westminster Abbey: the Lady Chapel, the almshouse and the huge landed endowment he provided for it. This was major enterprise with a £30,000 budget. Planning had begun five years before, in 1498. The foundation stone for the Lady Chapel was laid in 1503/4, and building works would continue until 1519, a decade after Henry died. Meanwhile some £5000 of the total budget was given to Abbot Islip to purchase manors and estates for an endowment to keep the memorial running: it was from this money that the abbot purchased Fenne and Scrane.

So it was that the Rochfords’ ancient manors, which they and their Fenne ancestors had held since the 1100s, became the property of Westminster Abbey. But there is something fishy about this sequence of transactions. Westminster Abbey valued the two manors at £34 a year, which is to say that was the profit they expected to get from them. What motivated John to sell his estates for only £460 – no more than fourteen years’ profits – after 350 years in the family? It is hard to imagine. Maybe he was duped, or maybe he was desperately in debt. On the face of things, it does not look to have been a very smart move.

*

Whatever happened here, it would not be the end of the story. John had an heir, also called John, who would stay on at Fenne – we’ll return to his brief, dark chapter shortly. But meanwhile, John’s half-brother Ralph had his own story unfolding at Stoke and Arley. All was not well.